Malaysia has tightened controls on the scrap-metal trade. A 15% export duty on ferrous scrap took effect in March 2021. The 2023 Customs (Prohibition of Imports) Order, reinforced in 2024, made SIRIM’s Certificate of Approval (COA) a legal prerequisite for customs clearance across a broader set of HS codes. Since mid-2024, a multi-agency enforcement drive has increased checks at ports. The policy mix has reshaped incentives, raised compliance costs, and favoured larger, better organised firms.

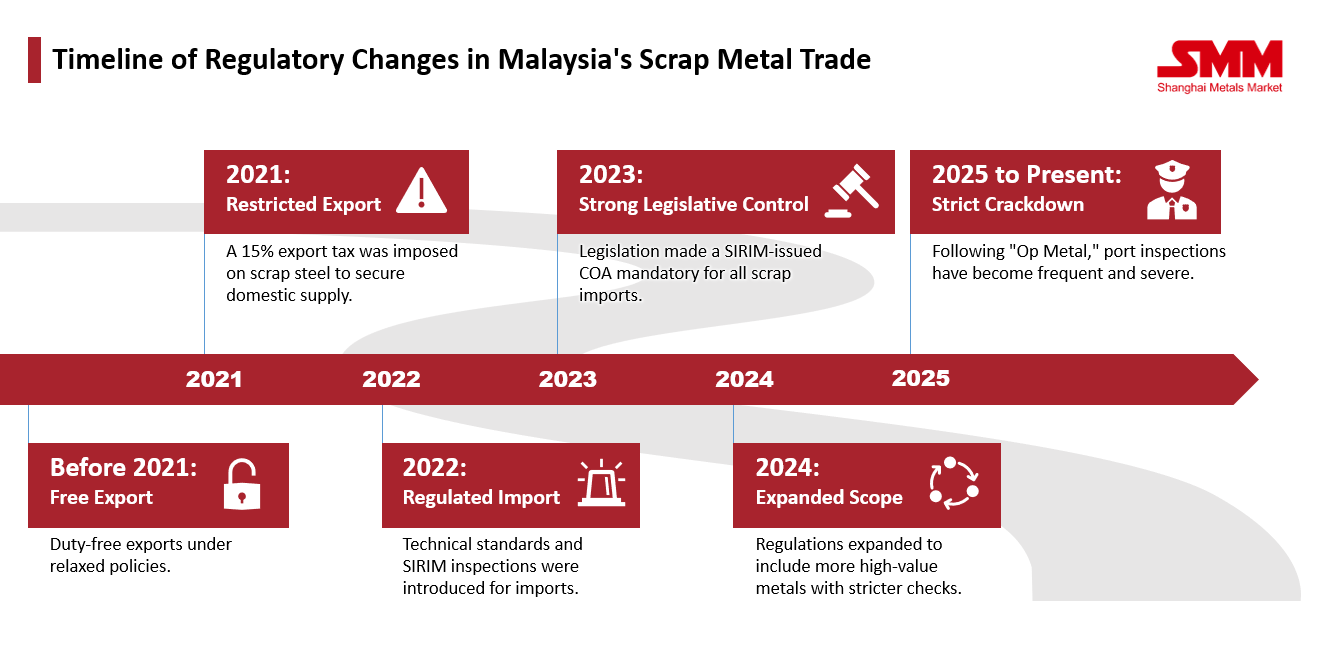

The Timeline of a Turnaround

The journey from the liberal export policies of the past to today's "strict-in, strict-out" environment was incremental, with each step setting the stage for the current high-enforcement landscape.

-

Before May 2018 — Laissez-faire baseline. In 2016 the government abolished a 10% export duty on scrap metal, loosening constraints on trade.

-

March 2021 — Export duty set at 15% for ferrous scrap (HS 7204) to secure feedstock for domestic mills.

-

January 2022 — First detailed import-inspection rules published. SIRIM named inspection and COA body. Shredded material under 5mm banned. Radiation cap set at background + 0.25 μSv/h.

-

April 2023 — The Customs (Prohibition of Imports) Order 2023 codified a “prior approval” regime. COA became mandatory before declaration. SIRIM formalised as the sole Permit Issuance Agency.

-

May 2024 — Scope widened. COA coverage expanded from 3 HS codes (7204, 7404, 7602) to 26, including nickel (7503), lead (7802), zinc (7902) and tin (8002). Document-cargo-form consistency checks tightened.

-

July 2024–present — “Op Metal” publicised. The anti-graft probe targeted misdeclaration schemes that dodged the 15% export duty. Joint inspections and random checks at ports became more frequent.

The pre-2018 setting

During Najib Razak’s cabinet (2009–2018) policy toward the scrap-metal industry was largely laissez-faire. In 2016 the government scrapped a 10% export duty on scrap, reflecting a pro-business stance.

The Economic Transformation Programme sought higher incomes by easing barriers for SMEs. Industry groups, including metal recyclers with strong Indian-Malaysian representation, engaged closely with officials. Their case was simple: heavy rules would sap dynamism; lighter rules and lower taxes would spread gains along the chain.

A pragmatic bargain emerged. Growth and jobs took priority, and some grey-area activity was tolerated. Unlicensed yards operated in many districts, and regulators often looked away. Policymakers viewed these firms as the system’s capillaries that might formalise over time.

The trade-off was clear. Faster expansion came with pollution risks, tax leakage and uneven standards. The same conditions that lifted activity also sowed the ground for a later policy turn toward tighter control.

The 15% Export Tax Pivot

The shift came in March 2021, when the government raised the export duty on ferrous scrap (HS 7204) from 0% to 15%. The change surprised exporters who had assumed open access to foreign markets.

The aim was explicit: secure feedstock for domestic steel mills as global prices rose and overseas demand strengthened. Large volumes of higher-grade scrap were leaving the country, tightening local supply. A 15% duty raised export costs and kept more material onshore.

The signal mattered more than revenue. Policy moved from permissive export promotion to active resource security. The market understood that looser rules would not return soon. The duty also paved the way for broader controls on the import side through the COA regime.

COA as the import gate

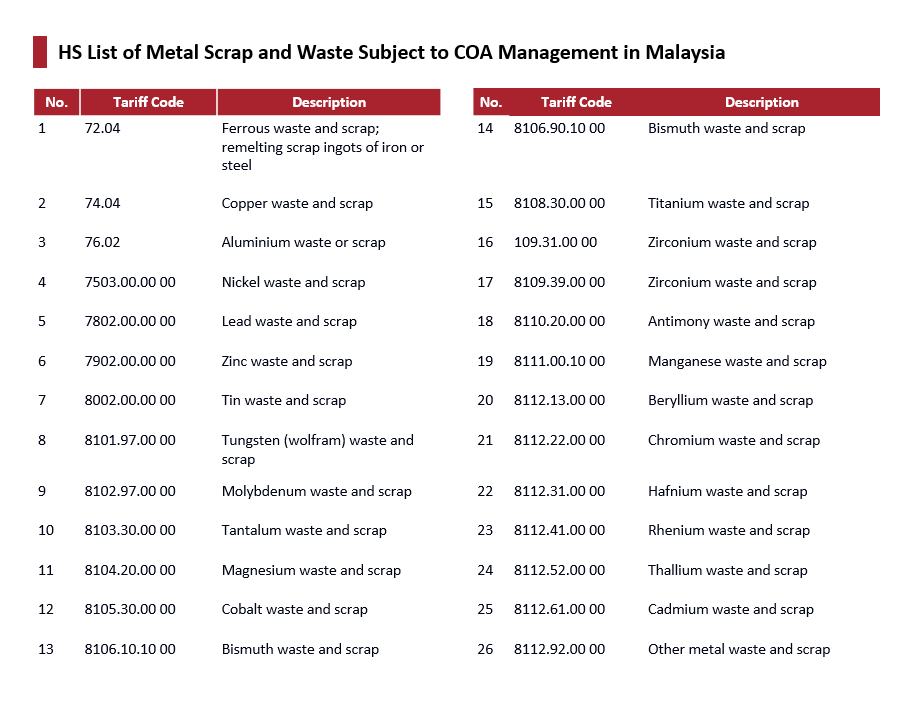

Malaysia then tightened the import side. A mandatory Certificate of Approval (COA), grounded in the Customs (Prohibition of Imports) Order 2023 and its 2024 amendment P.U.(A) 69/2024, created a full import-licensing regime.

Scope. Coverage widened by 23 HS codes. Beyond ferrous scrap, nickel (7503), lead (7802), zinc (7902) and tin (8002) now need approval.

Gatekeeper. SIRIM is the sole issuer. COA must be in hand before declaration and clearance; “declare first, certify later” no longer flies.

Inspection. Importers choose pre-shipment checks at origin or inspection on arrival. The former costs more to coordinate but reduces the risk of costly returns or destruction, so bigger, better-run firms prefer it.

Sources:SIRIM, SMM

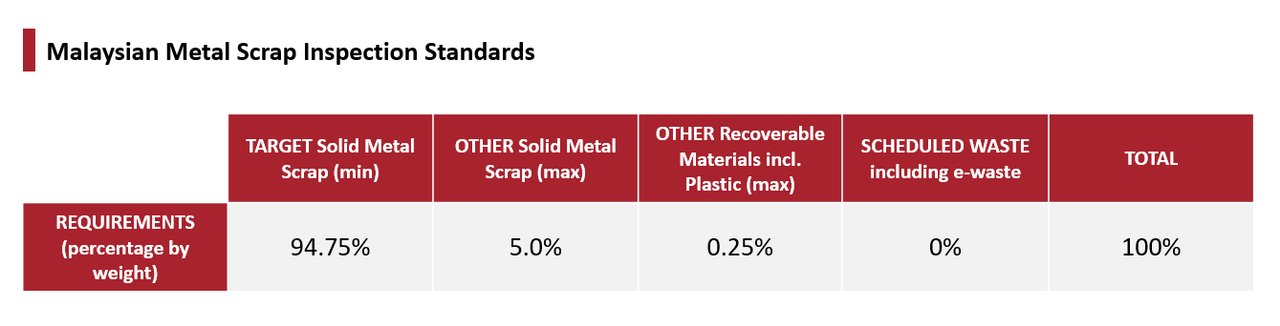

Inspection Under the Microscope: The Toughest Technical Thresholds Yet

Sources:SIRIM

Malaysia’s new rules turn scrap into a laboratory exercise. Imports must contain at least 94.75% of the principal metal; other metals are capped at 5% and non-metallics at 0.25%. Fines and shreds under 5mm are barred, to curb hidden contaminants and dust risks. Hazardous odds and ends—oils, paints, asbestos, sealed containers, medical waste, radioactive bits, even munitions—mean seizure of the lot.

The most contentious line is radiation: the dose rate at the package surface may not exceed background + 0.25 μSv/h, a tougher bar than the looser “twice background” common elsewhere. Traders grumble that geology and handheld meters can nudge clean cargoes over the limit. Compliance, they say, has become as much metrology as metallurgy.

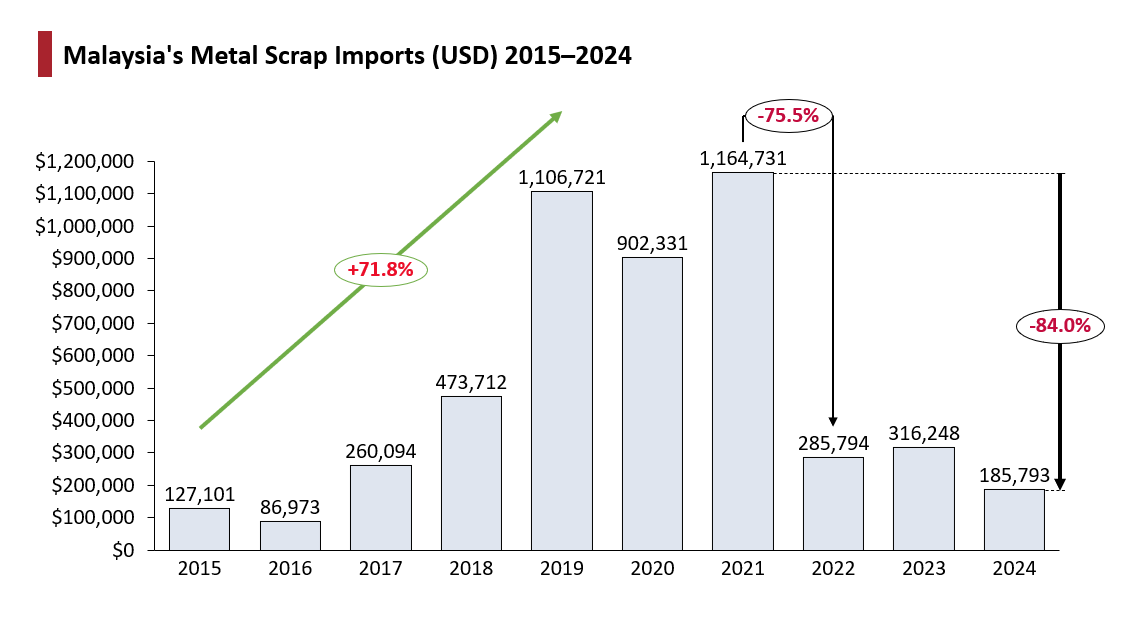

Sources: Trademap.org, SMM

The impact has been stark. Imports surged from 2017 to a peak in 2021. In 2022—when the COA regime bit—import value fell from over 1.16m to under 290,000, a drop of more than 75%. Volumes have stayed low since. Regulation, not price, now sets the pace. A high-barrier, compliance-led market is the new normal.

“Op Metal”: enforcement with teeth

A sweep dubbed “Op Metal,” led by the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission, has zeroed in on duty evasion. Since mid-2024 officials have probed schemes that misdeclared ferrous scrap as machinery or other untaxed metals to dodge the 15% export levy. Authorities say more than RM950m (about $202m) in revenue was lost over six years; assets of RM332m (about $70m) have been frozen or seized.

The message is blunt: zero tolerance. Error margins on export declarations have narrowed to near-nil. Though aimed at exporters, the campaign has also stiffened importers’ behaviour under the COA regime, tightening pressure on both sides of the trade.

SMEs squeezed, mills relieved

The new rules have split the market. Small and mid-sized traders bear most of the cost. Full COA compliance—inspection fees, bank guarantees and time delays—can wipe out margins. A single failed check risks a returned cargo and insolvency. Many smaller firms have exited or shifted lines, fuelling a “great reshuffle.”

Downstream users take a different view. Mills and smelters report cleaner feedstock, fewer hazardous contaminants and smoother operations. Higher, more predictable quality beats cheap but chaotic supply. Compliance has become a cost centre for traders and a quality upgrade for manufacturers.

The road ahead: compliance as strategy

Malaysia’s scrap market is mid-shift. Scale players—with steady supply, better sorting, tight documentation and capital—are set to gain share because they can absorb compliance costs.

For everyone else, shortcuts now destroy value. Build systems: audit trails, supplier vetting, pre-shipment checks, and radiation and composition records that stand up at the quay. Deals will clear on evidence, not just price. The winning bid is the one backed by paperwork that a regulator can trace end to end. The question now is whether Malaysia's high-stakes gambit—sacrificing scrappy SMEs for industrial stability—will become a model for other resource-rich nations in the region.

![[NPI Daily Review] The Market Was Mainly Driven by Restocking to Meet Immediate Needs; High-Grade NPI Prices Held Steady](https://imgqn.smm.cn/usercenter/CjEnN20251217171733.jpg)